The Hodgkinson gold rush, 1876

The port of Cairns and Old Smithfield township were established in late-1876 as supply towns to serve the diggers that had been part of the mad rush to the Hodgkinson goldfield earlier that year.

The story of the Hodgkinson began in two years earlier in September 1874, when James Venture Mulligan was travelling through Gugu Djungan country. Mulligan was an Irish-born explorer and prospector who arrived in Australia in 1860 at the age of 22.1 He moved to Queensland in 1867 and headed north prospecting for gold, arriving at Georgetown on the Etheridge goldfield in the early 1870s.

Mulligan’s 1873 Expedition to the Palmer

After William Hann’s 1872 expedition found traces of gold at the Palmer River, Mulligan led an expedition there the following year.2 His party consisted of Albert Brandt, James Dowdell, David Robinson, Peter Abelsen (also known as Peter Brown) and Alexander Watson. When they returned with their saddlebags packed with 102 oz of alluvial gold, Mulligan was given a £1,000 reward, and the news sparked a rush of 30,000 miners to the new field.3 The Palmer River became Queensland’s richest alluvial field.

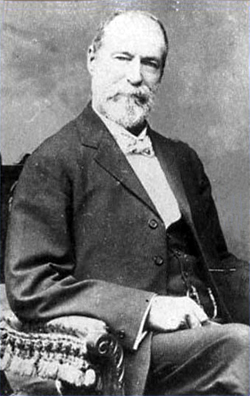

James Venture Mulligan, 1905.

Photo by Poulsen of Brisbane, lent by T.J. Byers, Hughenden.

Mulligan’s 1874 Expeditions

In 1874 Mulligan and party undertook three prospecting expeditions. The first left from Edwardstown on the Palmer in June and explored the St George River.4

The second left Palmerville on 6 August and travelled via the St George River to the Mitchell River.5 On 2 September they rode south-east for 18 miles through open forest, box flats and ridges of iron-bark, before encountering a large, deep tributary which flowed into the Mitchell. In the distance was an impressive conglomerate and sandstone bluff which Hann had reported seeing two years earlier, but had not visited. Mulligan found “great pleasure traversing new country where no white man has trod before” and relished new scenes and fresh discoveries, so he followed the river upstream and camped opposite this imposing massif.6

The Gugu Djungan people called it Ngarrabullgan, the place where a malicious spirit ancestor, the Eekoo, lived. Mulligan ascribed an Anglo-Australian name to the mountain and, at the insistence of his party, named it after himself. He named the river they were camped on the Hodgkinson, in honour of his friend and fellow explorer, the member for Burke, William Oswald Hodgkinson.7

The next day they panned for gold in the sand on the rocky river bars and found traces of colour in their pans. On 5 September they spent the day prospecting, but reported that “colors and shotty specks are all that is obtainable”.8 Mulligan was disappointed and wrote “there was no prospect for anything payable here, only for fattening cattle". He noted "We are disgusted with the sight of such nice round hills and mountains passed by, and yet no show of gold or even quartz”.9 By the 21 September Mulligan and his party were back at Palmerville.

Ngarrabullgan / Mount Mulligan.

Photo by Kyle Taylor, flickr.

Mulligan’s 1875 Expedition

In 1875 Mulligan was appointed by the Queensland colonial government to lead a prospecting expedition, with the promise of £500 funding and £1,000 reward for the discovery of payable gold. Mulligan’s party consisted of his old colleagues James Dowdell and Peter Abelson, as well as government surveyor Frederick Warner, who had been a member of Hann’s 1872 expedition, William Harvey, Jack Moran and an Aboriginal guide, whom the Anglo-Australians referred to as ‘Charlie’. The Mulligan Exploring Party left Cooktown with 22 horses, on 29 April and travelled extensively around southern Cape York, covering almost 2,000 kilometres over nearly five months, including a visit to the Hodgkinson where they found a little gold near the mouth of McLeod Creek.10

The Mulligan Exploring Party returned to Cooktown for resupply at the end of September and Mulligan asked for additional government funding.11 He was given £500 as promised for the expedition he had just completed, but no further monies were forthcoming and, as they had not found any payable deposits, he was instructed to disband the party.12 Mulligan decided to fund his own prospecting expedition and return to the Hodgkinson.13

Mulligan’s 1876 Expedition

Mulligan, Warner and Ablesen left Cooktown for Byerstown at the end of October 1875, where they purchased 35 horses. They set off for the Hodgkinson on 31 December. On the 18 January 1876 they established a camp on the Hodkinson, a little way south of Mount Mulligan. For the next five weeks they prospected the creeks and gullies, finding patches of alluvial gold and plenty of quartz outcrops, but without a pestle and mortar they were unable to ascertain the quality of the reef gold.

On the evening of 26 January, Mulligan’s men were in camp when they heard horse bells about a mile away. Abelson went to investigate and was met with a rifle shot from prospector Hugh Kennedy, who assumed Abelson was an Aboriginal man attempting to spear the horses in the twilight. Fortunately, the Snider bullet missed Abelson and he was not injured. Kennedy, along with his colleague William Williams, told Mulligan they were part of Billy McLeod’s party, and they had been finding gold in the Hodgkinson area for several weeks.14 Mulligan and McLeod agreed to share the £1,000 reward for discovering the new field.

In early March the grass around Mulligan’s camp caught fire, destroying their tents and supplies, leaving them with only a little flour and one roll of meat, so once the Wet Season rains abated and the Mitchell was low enough to cross, the party made a hurried return to the Palmer. On 10 March they reached Byerstown and broke the news of the new goldfield.15

Mulligan thought the Hodgkinson “will be one of the largest reefing districts in the colonies”, but he noted the alluvial gold was only found in patchy dabs. He warned that “miners must not expect the gold to be got without working hard for it – I never worked harder for the little we got. Our party of three only obtained 3 lbs., besides some specimens for our ten weeks' trip. I think it better to publish this fact, so that diggers will not be deceived by exaggerated accounts. Great excitement prevails at Cooktown, and I am sure that many miners will meet with disappointment”.16

The Hodgkinson Goldrush

Despite Mulligan’s warnings, the news aroused intense interest and excitement.17 When McLeod and party arrived in Cooktown on 27 March 1876 and confirmed Mulligan’s discovery, hundreds of miners abandoned their claims on the Palmer and set out for the Hodgkinson. Mulligan requested a police escort to protect him from Aboriginal attack, and set out to mark a dray road to the Hodgkinson, followed by hordes of diggers. The Palmer River Goldfields Warden Phillip Sellheim was ordered to supervise the rush, and he ordered Assistant Goldfields Warden W.R.O. Hill to the Hodgkinson. Flooding in the Mitchell meant it was 19 April before he reached the new field.18

Hill found 2,000 miners, many of whom were angry about the lack of alluvial gold. 700 men had already left the field to return to the Palmer and most of the remaining men were destitute. Food was in short supply and the sparse rations that were available were extortionately priced, with beef at 1s per lb and flour at 2s.19 Mulligan was accused of misleading the diggers, and rumours circulated that he had spent much of 1875 finding the best alluvial gold and had already taken over a hundredweight to Cardwell.20 There were threats of a riot and calls for Mulligan to be hanged. Warden Hill only stayed for two days before returning to Cooktown, where he sent a telegram to the Minister for Mines noting that the situation was grim and that the rush of alluvial miners must stop or starvation was possible.21 The government ordered notices be printed and posted at ports notifying miners that “the new rush is a total failure – All the diggers are making their way back and great dissatisfaction prevails amongst them”.

Reef miners, however, realised the potential of the new field, and there were calls for a dray road to be constructed from Cooktown so that stamper batteries and cyanide plants could be brought to the field. The government announced that the telegraph line would be extended to the new field and tenders were called for a road construction party and a mail service. In June 1876, there were between 1500 and 2000 miners on the field, the Hodgkinson Minerals Area was proclaimed, the town of Thornborough, named in honour of the Premier, George Thorn, was declared and a post office opened. At the end of the month, Goldfields Warden Howard St George arrived to issue miner’s rights and sort out disputes over claims. George Clark cut a track from the Cardwell-Etheridge Road to the Hodgkinson, making the trip to coast just 220 kilometres and Mr. P. Martin relocated his crushing plant from Georgetown. The dray road was completed from Cooktown, and numerous shops and stores opened up. Drovers brought mobs of cattle, five butchers opened and the price of beef fell to 4d per lb.22 Parties went out to look for a suitable track to the telegraph station at Junction Creek.

Nevertheless, the Hodgkinson was still very isolated, transport costs were high and flooding in the Mitchell River regularly closed the road. When two of Mulligan’s party, Jack Moran and Mr. Harvey were prospecting on the mountain range 80 kilometres to the east of Thornborough at the end of June, they saw the sea from the top of the range. The miners wanted to know if a shorter road could be opened up to the coast at Pana Wangal (Trinity Bay).

| Go to the next section ⇒ Pack Tracks to the Hodgkinson. | |

|

This webpage is an excerpt from the upcoming book Old Smithfield: Barron River township (1876-1879) by Dr Dave Phoenix. Find Out More Here |

Featured Artefacts from Old Smithfield:

-

1. James Venture Mulligan (1837, Co. Down, Ireland–1907, Mount Molloy, Queensland). ↩

-

2. William Hann, Copy of the diary of the Northern Expedition under the Leadership of Mr. William Hann, (Brisbane: Government Printer, 1873). ↩

-

3. "The Miner", Queenslander, 11 October 1873: 6. ↩

-

4. "Our Summary for Europe", Queenslander, 17 April 1875: 4 ↩

-

5. “The Palmer Gold-field”, Queenslander,

24 October 1874: 9. ↩ -

6. Robert Logan Jack, Northmost Australia, Volume II. ↩

-

7. William Oswald Hodgkinson

(1835, Handsworth, UK–1900, Brisbane).

Hodgkinson was the first member for the electorate of Burke, holding the seat from its establishment in 1873 until 1875 when he resigned to take up the leadership of the North-West Queensland Expedition. ↩ -

8. “The Palmer Gold-field”, Queenslander,

24 October 1874: 9. ↩ -

9. Robert Logan Jack, Northmost Australia, Volume II. ↩

-

10. Expedition in Search of Gold and other Minerals in the Palmer District by Mulligan and Party." Brisbane: Government Printer, 1876.) ↩

-

11. "Cooktown", Brisbane Courier,

28 December 1875: 6. ↩ -

12. Memorandum, Department of Mines,

31 March 1875, 75/2022 A/8711, Queensland State Archives. ↩ -

13. Brisbane Courier, 28 December 1875: 6. ↩

-

14. “The New Gold-field”, Queenslander,

1 April 1876: 23. ↩ -

15. “The Mulligan M'Leod & Party's New Gold Field”,

Northern Miner (Charters Towers), 29 March 1876: 2. ↩ -

16. “The New Gold-field”, Queenslander,

1 April 1876: 23. ↩ -

17. “The New Gold-Field”, Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, 25 March 1876: 3. ↩

-

18. Memorandum W.R.O. Hill to the Minister for Mines, dated 24 April 1876, 76/9 MWO, 13A/G1. Queensland State Archives. ↩

-

19. “The Hodgkinson River Gold-Field”,

Argus (Melbourne), 26 Apr 1876: 6. ↩ -

20. Cooktown Herald, 12 April 1876. ↩

-

21. Telegram from W.R.O. Hill to Minister for Mines, 76/9 MWO, 13A/G1, Queensland State Archives. ↩

-

22. “The Miner”, Queenslander, 29 July 1876: 27. ↩